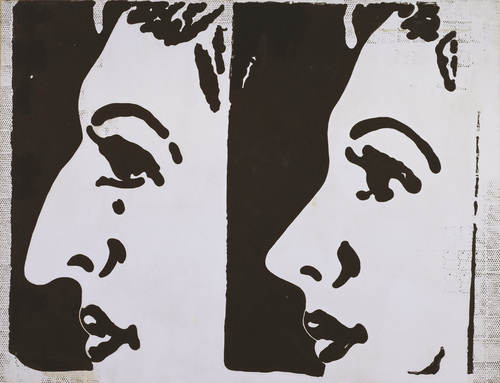

Still from "The Transfiguration" video/installation by Matt Pyke, 2009

Oct 31, 2011

The Transfiguration

Oct 21, 2011

Best Wishes

Portland artist MK Guth stands with her braids inside the Cosmopolitan’s P3 Studio.

Photo: Leila Navidi

Artist MK Guth's Rapunzel-like interactive performance/installation Best Wishes recently ended its run at the Cosmopolitan Hotel's P3 Studio in Las Vegas. The work invited gallery visitors to write wishes and desires onto strips of fabric that were woven into an ever-growing braid of synthetic, blond hair attached to Guth's head. The braids grew to more than 200 feet, hanging from the ceiling and extending through two rooms of the studio.

Photo by Kristen Peterson

Guth related her work to the way visiting Las Vegas tends to involve a wish, a dream or a hope. People come to Las Vegas to gamble, see shows, shop or experience the fantastical, so Guth asked people to share their wishes on white ribbons she then had braided into her hair. "Some people write one word. Some write a tome...I have the burden, literally, of other people’s concerns."

A local newspaper, reporting on the installation, described a tourist from Florida who came to Las Vegas to try and assuage her negative feelings of a divorce she was going through. In the gallery the tourist "ended up chronicling [her feelings], along with her dreams and hopes, on a piece of cloth for Guth. Having them braided into the artist's hair probably won't help them come true but at least it made her feel better."

The fictional Rapunzel was trapped by an old witch, but the contemporary Rapunzel is trapped by her own internal dilemmas. In the fairy-tale, hair is the means by which Rapunzel can be rescued from her entrapment and Guth maintains a similar agency for hair in her own work. Not only does Guth literally transfer fears, burdens, and wishes onto her own shoulders, but the braids subsume people's wishes and worries via the act of weaving, a common metaphor for life.

I Still Feel the Same, 2008

This is not the first time Guth has worked with weaving words into braided lengths of artificial hair extending from her head. Her 2008 performance piece I Still Feel the Same at the Yerba Buena Art Center in San Francisco similarly asked visitors to write on a piece of paper, however this time their thoughts were about the idea of 'feminism.' The braid was then cut after two days and was presented as an object in the group exhibition The Way That We Rhyme: Women, Art and Politics.

For Tiles of Protection and Safe Keeping at the 2008 Whitney Biennial, visitors responded to the question, "what is worth keeping?" The curators described MK Guth as "reimagin[ing] traditional fables and popular fantasies, inserting new, hybrid mythologies into the public realm as vehicles for agency, empathy, and social engagement."

Tiles of Protection and Safe Keeping, 2008

While Guth's performance/installations lack a certain sophistication in their execution, there is something inherently pleasing about them. If fairy tales often start with a wish, here it is not some elf who comes in the night to spin straw into gold, but rather our own intentions -- our literal incantations -- that ask to manifest transformation and re-invigorate magical experience.

Oct 11, 2011

Exhibition: A Short History of Facial Hair

David McDiarmid (1952-95) was an artist, DJ, graphic designer, fashion designer and queer political activist. He was born in Australia and lived and worked in Sydney before moving to New York where he worked from 1979 until 1987. He died in Sydney of HIV Aids-related illness in 1995.

In 1993 McDiarmid wrote and performed an essay, accompanied by 35mm colour slides, entitled A Short History of Facial Hair in which he pulled together his personal fashion, grooming and adornment story and his political and sexual history, representing a twenty-year period of his life and times.

A Short History of Facial Hair has been digitised and re-created as a film by the Fashion Space Gallery, directed by Hermano Silva. Silva is a Brazilian photographer who lives and works in Berlin. He is a graduate of the MA program in Fashion Photography at London College of Fashion. A Short History of Facial Hair is screened in conjunction with a display of McDiarmid’s Rainbow Aphorisms – a suite of fierce and seductive digital art works created in 1994-5.

The exhibition has been jointly curated by Dr. Sally Gray, University of New South Wales, Sydney and Fashion Space Gallery Curator, Magdalene Keaney. On view at the Fashion Space Gallery until October 29, 2011.

C. Moore Hardy - David McDiarmid - 1993

David McDiarmid - Facial Hair... from Trade Enquiries - 1978

Beautiful, hard hitting and humorous A Short History of Facial Hair is an interrogation of McDiarmid’s appearance as it changes from hippy to clone, to Gay Liberation activist, sexual revolutionary, hustler, dance floor diva, and ultimately, to HIV–positive queer subject - his self styled “Toxic Queen.” He traces how gay politics changed during what he described as “an extraordinary time of redefinition and deconstruction of our identities from camp to gay to queer.” The work explores links between art, identity, politics, dress and adornment.

Photographer unknown - David McDiarmid - 1981

Photographer unknown - David McDiarmid - 1986

Oct 10, 2011

Andy Warhol's Wig - a defining art object

"Warhol's wig depended on him. Abandoned in the vitrine, the prosthesis looks like a flattened jellyfish, a splayed broom, an apology." ~ Wayne Koestenbaum for Artforum 1998.

Self-portrait (Fright Wig), 1986

Many identify Andy Warhol by his trademark wig, a variously grey to silver contraption that sat uneasily upon his head. And sat it did, rather uncomfortably, with no pretension of being real. The ubiquitous two-tone hairpiece was not a simple fashion item, but rather a fundamental device for the creation and self-mythologized persona of "Andy Warhol," ultimately rendering him brand-like.

Warhol, says Baudrillard: “never aspired to anything but this machinic celebrity, a celebrity without consequence which leaves no trace” – the “perfect artifical personality;” “a kind of hologram;” or “otherness raised to perfection.”1

Warhol's self-created "otherness" was achieved, in part, through a delineation of his image via "the wig." But there was not simply one wig, there were hundreds of wigs, as it turns out. Andy never threw a wig away and when he died in 1987, they were found in an assortment of boxes and envelopes. There are 40 alone archived in the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburg, PA.

Paige Powell, John Sex and Men in Andy Warhol Wigs, 1983.

©2010 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

©2010 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The wigs were made from hair imported from Italy and sewn by a New York wig maker. Labels on the inside crown read, "HAIRPIECE, Original by Paul." It was one of these that Warhol framed and gave to Jean Michel Basquiat as an artwork.

Thursday, December 19, 1985

Tina Chow called and said there was a dinner for Jean Michel at 9:00, just really small. Jean Michel had his mother and her friend there. I brought him a present, one of my own hairpieces. He was shocked. One of my old ones. Framed. I put '"83" on it but I don't know when it was from. It's one of my Paul Bochicchio wigs. It was a "Paul Original."

Wigs are personal and rather disgusting, but Warhol's instinct to give Basquiat one of his, as if it were an ordinary collectible item, turned out to be quite astute. In 2006, a Warhol wig sold for $10,800 at a Christie's auction.

Warhol began to wear wigs in the 1950s to cover up his early male pattern baldness and gradually graying hair. (He also had his nose "planed" in 1956.) The first wig was a mousy brown, but he moved into yellow-blond, then platinum, and ultimately settled on shades of grey/silver, wearing the wigs with his existing darker hair sticking out at the bottom. Warhol settled on grey because if you always appear old no one knows how old you really are.

Warhol began to wear wigs in the 1950s to cover up his early male pattern baldness and gradually graying hair. (He also had his nose "planed" in 1956.) The first wig was a mousy brown, but he moved into yellow-blond, then platinum, and ultimately settled on shades of grey/silver, wearing the wigs with his existing darker hair sticking out at the bottom. Warhol settled on grey because if you always appear old no one knows how old you really are.

The wigs changed and slipped.

The thing about the wig is that the more it looked like a wig, the less it looked like a wig. Was it a wig? Because the wigs that look like wigs are the ones that attempt to look like real hair, and Andy's never looked like a wig."

~ Kicking the Pricks, Derek Jarman

Despite the obviousness of the sham, when Warhol's wig was snatched from his head on October 30, 1985 it was his worst nightmare come true:

"I guess I can't put off talking about it any longer. Okay, let's get it over with. Wednesday. The day my biggest nightmare came true... I'd been signing America books for an hour or so when this girl in line handed me hers to sign and then she - did what she did... I don't know what held me back from pushing her over the balcony. She was so pretty and well-dressed. I guess I called her a bitch or something and asked how she could do it. But it's okay, I don't care - if a picture gets published, it does. There were so many people with cameras. Maybe it'll be on the cover of Details, I don't know... It was so shocking. It hurt. Physically... And I had just gotten another magic crystal which is supposed to protect me and keep things like this from happening..."2

Self-Portrait (Passport Photograph with Altered Nose), 1956

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

But Warhol's wig was more than just a cover-up for baldness or a device to devise a distinct identity; the wig had roots in the deep insecurities of the Catholic, homosexual Andy Warhol. In a 2001 issue of American Art, Bradford Collins describes a number of ways that Warhol was tortured by his appearance, describing Warhol as having an "image of himself as severely flawed."3 Warhol's desire to alter his appearance related to a belief that ugliness was a barrier to both fame and to erotic encounters.

While on the one hand he wanted to appear attractive to men, he also understood that the commercial success he so desired required him to appear less gay. "Emile de Antonio, had convinced him that if he wanted to succeed in the New York art world - then both antibourgeois and homophobic - he would not only have to hide his commercial activities to conform to the profile of the avant-garde artist, but would also have to follow the example of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns and give up his 'swish' behavior and 'try to look straight.'"4

But what signifies beauty? or gayness? Warhol began to explore cultural notions of beauty, identity, and refashioning ones appearance early in his career. The idea of the "make-over" can be seen not only in a series of Before and After paintings that Warhol created in the early 1960s based on classified ads selling nose jobs, but also in a doctored passport photo from 1956. Its hard not to read Before and After as a "deflected and disguised self-portrait,"5 knowing that Warhol had had his own nose re-shaped. Three other works at this time, Wigs (1960), Bald? (1960) and Nine Ads (1960), also point to both a personal concern with appearance modification and broader paradigms of beauty. However, it is camp that "served as the theatrical "bracketing" that made confession into a social event, and rendered the marketing of body transformations into art."6

Before and After, 1961, MOMA

Thus the wig was more than a wig. It symbolized what Warhol wanted to become as well as what he felt compelled to hide. The style icon Daphne Guinness speaks about how clothes can be used, like armor, to hide behind, to protect oneself, even as they ultimately garner attention. It was in this same manner that Warhol's wig allowed him to hide in plain sight.

1. Dr. Gerry Coulter, Jean Baudrillard’s Andy Warhol Survives Euro Pop, Euro Art and Beyond, Fall 2008.

2. www.warholstars.org/chron/

3. Bradford R. Collins, "Dick Tracy and the Case of Warhol's Closet: A Psychoanalytic Detective Story," American Art (Autumn, 2001).

4.. Ibid.

5. Caroline A. Jones, Machine in the Studio, University of Chicago Press, 1996, page 225.

6. Caroline A. Jones, Machine in the Studio, University of Chicago Press, 1996, page 225-6.

7. Bradford R. Collins, "Dick Tracy and the Case of Warhol's Closet: A Psychoanalytic Detective Story," American Art (Autumn, 2001).

Oct 6, 2011

Beards and Moustaches

Every two years facial hair enthusiasts converge at the World Beard and Moustache Championship. Men compete in a variety of categories that include Dali, imperial, and freestyle for moustaches and natural, Fu Manchu, Musketeer, and Verdi for beards.

But some of the best pictures of these hirsute gentlemen were taken by Matt Rainwaters at the 2009 competition in Anchorage, Alaska. Scroll and enjoy these images from his series Beardfolio.

Finland’s Juhana Helmenkalastaja - 2011 Winner of Dali moustache - Photo by Banjo Media

Germany's Dieter Besuch - 2011 Winner of the Partial Beard Freestyle - Photo by Gregory Fett

But some of the best pictures of these hirsute gentlemen were taken by Matt Rainwaters at the 2009 competition in Anchorage, Alaska. Scroll and enjoy these images from his series Beardfolio.

Cory Plump, an Austin Facial Club member and garibaldi contestant.

Steven Raspa and his beard Prepostero

San Franciscan Jack Passion placed third this year (2011) with his long, red natural beard.

Oct 3, 2011

Fashion's Allusion to Hair

Alexander McQueen - Coat

Eshu, autumn/winter 2000–2001

Black synthetic hair

Eshu, autumn/winter 2000–2001

Black synthetic hair

Pierre Balmain - Fall 2011

Steffie Christians - Spring 2012

Jean-Charles de Castelbajac - Spring/Summer 2009

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)